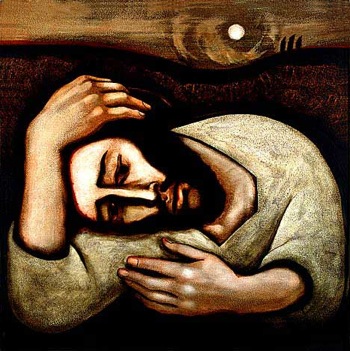

Did not our hearts burn within us as he explained the scriptures to us. (Luke 24:32)

Today's Gospel has surprisingly much about words and conversation in it. There is discussion, debate, prophecy, explanation, rebuke, exhortation and more. At a deep level it is about language and symbolism, and the encounter through these to the Risen Christ.

And there is a striking comparison made here by St Luke, which is sadly lost in this translation. Early on, Jesus rebukes the disciples for being "slow of heart" - our translation just has "slow to understand". I think this is a pity, because at the end of the Gospel, the disciples echo Jesus's words - “did not our hearts burn within us as he explained the prophecies to us?”

It sees this would be a good point for me to preach for the first time on the new translation of the mass, because today's Gospel makes the points for us.

First, people rightly ask 'why a new translation'? Well, there are several reasons. The first is that the present translation is 40 years old, and English is a living language and has changed much in this time. A revision is long overdue. Secondly, while Latin has not changed, the Latin missal has - there are more saints, greater variety of prayers, all which need to be brought into English.

But there is further reason. The translation we know so well was produced in something of a hurry, and took a particular approach to translation which simplified the meaning of the original.

Let me explain.

Words in different languages generally have direct translations, but the ways in which we use those words may differ. As a simple example, consider what we say when we answer the phone. In English we say “Hello” (a word which was made up for the telephone) but in Italian we would say “Pronto” - word which really means ‘Ready!’. Similarly, when we greet someone in French we would say “Bonjour” - that is “Good Day” - which sounds old fashioned and formal in English (unless you are Australian, of course). So, a word for word translation often does not work - you will know this very well if you’ve ever tried to follow the instructions for self-assembly furniture!

When the present Missal was translated, sometimes a quite flexible approach was taken to the language, and the translators worked hard to make the English immediately understandable. This meant that sometimes they lost some of the imagery and especially the Biblical references.

Here’s a couple of examples. In the Latin, when the priest says “The Lord be with you” we all reply “And with your spirit”. This phrase is used many times by St Paul in his letters. The translators asked themselves “what does this mean?” - clearly something like “with you, too” - that sounds too informal, so they settled on “And also with you” (and so lost the reference to the Spirit, and to the writings of St Paul).

Similarly, before we receive communion, in Latin we would say “Lord, I am not worthy that you should come under my roof, but only say the word and my soul shall be healed”. These remind us of the words of the Centurion (in St Luke’s Gospel 7:6) who asks Jesus to heal his servant. The translators 40 years ago removed the reference to the roof - and just said “receive you”. This was probably meant to suggest receiving a guest into our houses, but I think we have come to assume it just refers to communion. And the reference to our soul was lost too.

The new translation restores these references to Scripture and recovers a lot of the imagery and depth which is in the Latin but which was simplified away in the English. It may mean that to begin with we will find the new translation a bit cumbersome and awkward, though I am sure that will pass, and we will find it enriching and inspiring in the longer term.

But for the most important point, we need to return to today’s Gospel. The hearts which were slow to understand became also the hearts which burnt within when the words were explained to them - but it was in the breaking of bread that they recognised the risen Lord.

The meaning is very clear. The words are important, very important - but it is the heart which burns with understanding and insight, not just the mind.

And we recognise Jesus fully, in the mass, not in the words we utter, but in the sacrament which we share.

The most famous play of the playwright Samuel Becket is called “Waiting for Godot”. When it was published and first performed in the early 1950s it caused something of a storm. By the 1970s when I studied it for A level, it had become something of a classic.

The most famous play of the playwright Samuel Becket is called “Waiting for Godot”. When it was published and first performed in the early 1950s it caused something of a storm. By the 1970s when I studied it for A level, it had become something of a classic.

We celebrate today the Feast of Christ our King. It is the culmination of the Church year as we celebrate Christ gathering all things to himself and ruling as Lord of all creation.

We celebrate today the Feast of Christ our King. It is the culmination of the Church year as we celebrate Christ gathering all things to himself and ruling as Lord of all creation.

In these words, Christ conveys to us two essential truths about the Church.

In these words, Christ conveys to us two essential truths about the Church.

Why are you men looking into the sky? (Acts 1:11)

Why are you men looking into the sky? (Acts 1:11) In a

In a